Permanent income hypothesis

The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) is a theory of consumption that was developed by the American economist Milton Friedman. In its simplest form, the hypothesis states that the choices made by consumers regarding their consumption patterns are determined not by current income but by their longer-term income expectations. The key conclusion of this theory is that transitory, short-term changes in income have little effect on consumer spending behavior.

Measured income and measured consumption contain a permanent (anticipated and planned) element and a transitory (windfall gain/unexpected) element. Friedman concluded that the individual will consume a constant proportion of his/her permanent income; and that low income earners have a higher propensity to consume; and high income earners have a higher transitory element to their income and a lower than average propensity to consume.

In Friedman's permanent income hypothesis model, the key determinant of consumption is an individual's real wealth, not his current real disposable income. Permanent income is determined by a consumer's assets; both physical (shares, bonds, property) and human (education and experience). These influence the consumer's ability to earn income. The consumer can then make an estimation of anticipated lifetime income.

Transitory income is the difference between the measured income and the permanent income. It can be calculated simply by subtracting the measured income and the permanent income.

There is a corollary to the permanent income hypothesis named the permanent production hypothesis. This hypothesis stipulates that the choices made by producers regarding their production patterns are determined not by their present term capital cost but by their longer-term capital cost expectations. The key conclusion of this theory is that transitory, short term changes in capital costs have little effect on production behavior.

Proof

Here is the permanent income hypothesis and the permanent production hypothesis in a nutshell. We define variables that will be used in this proof:

= Money Supply (Measured in Dollars)

= Money Supply (Measured in Dollars)

= Velocity of Money (Measured in 1 / years)

= Velocity of Money (Measured in 1 / years)

= Price Level (Measured in $ / item)

= Price Level (Measured in $ / item)

= Quantity of Transactions (Measured in items / year)

= Quantity of Transactions (Measured in items / year)

= Savings (Measured in Dollars / year)

= Savings (Measured in Dollars / year)

= Income (Measured in Dollars / year)

= Income (Measured in Dollars / year)

= Nominal Annual Interest Rate

= Nominal Annual Interest Rate

= Real Interest Rate

= Real Interest Rate

= Inflation Rate

= Inflation Rate

= Nominal Gross Domestic Product (Measured in dollars / year)

= Nominal Gross Domestic Product (Measured in dollars / year)

= Real Gross Domestic Product (Measured in dollars / year)

= Real Gross Domestic Product (Measured in dollars / year)

= Debt

= Debt

= Noninterest Income (Dollars / year)

= Noninterest Income (Dollars / year)

= Tax Rate

= Tax Rate

= Cash

= Cash

= Inverse Leverage Ratio (Total Equities Outstanding / Total Debt Outstanding)

= Inverse Leverage Ratio (Total Equities Outstanding / Total Debt Outstanding)

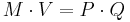

Start with the Fisher equation of exchange:

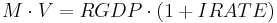

is normally replaced with nominal GDP. Nominal GDP is simply real GDP multiplied by 1 plus the inflation rate and so.

is normally replaced with nominal GDP. Nominal GDP is simply real GDP multiplied by 1 plus the inflation rate and so.

under Friedman was considered to be money supply. But it doesn't take a genius to figure out that the federal reserve can "print" all the money it likes - if the credit that it extends does not make it into the private sector then you get no GDP. And so let us say that

under Friedman was considered to be money supply. But it doesn't take a genius to figure out that the federal reserve can "print" all the money it likes - if the credit that it extends does not make it into the private sector then you get no GDP. And so let us say that  (money supply) should be replaced with

(money supply) should be replaced with  (debt in dollars).

(debt in dollars).

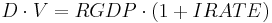

What is  ? At first glance

? At first glance  should be equal to income. You need income to buy the goods represented by GDP. And so:

should be equal to income. You need income to buy the goods represented by GDP. And so:

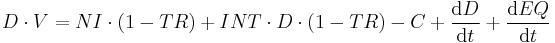

But not all income is spent, some is saved and some pays taxes. Likewise not all purchases are made out of current income, some purchases are financed with debt or in the corporate sector equities. Because the units for GDP (likewise for  ) are $ / year, we look at the change in debt and equities (

) are $ / year, we look at the change in debt and equities (  and

and  ) to represent new financing within that year.

) to represent new financing within that year.  represents all previous debt incurred in previous years and

represents all previous debt incurred in previous years and  represents all outstanding equities for reasons that will become apparent.

represents all outstanding equities for reasons that will become apparent.

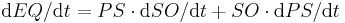

Equity ( ) is the total market capitalization of the U. S. market. The total market capitalization is affected by two variables - shares outstanding

) is the total market capitalization of the U. S. market. The total market capitalization is affected by two variables - shares outstanding  and price per share

and price per share  .

.

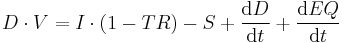

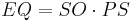

And so:

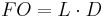

Also  is simply debt times the inverse leverage ratio

is simply debt times the inverse leverage ratio

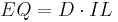

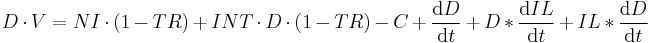

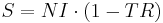

Savings  represents zero term financial assets or cash

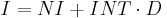

represents zero term financial assets or cash  . Income can be broken into two parts, interest income and non-interest income in this way:

. Income can be broken into two parts, interest income and non-interest income in this way:

Here we will make the assumption that all interest income is taxable.

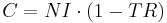

In a closed economy (no foreign trade), the after tax non-interest income per year will equal the sum of all zero term financial assets or cash

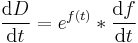

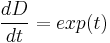

Solving the differential equation for  gives:

gives:

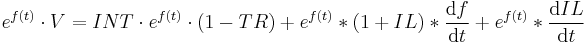

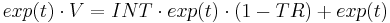

The interest rate has a real and inflation component, and so breaking up the interest rate into its components gives:

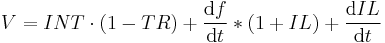

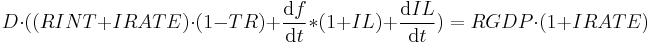

Back to the Fisher equation:

And so the conclusion is simple, if you want to raise real GDP, you raise the real interest rate, you decrease the leverage ratio (sell more equities), you increase population, and you lower the tax rate. This works well enough until you run a huge trade imbalance (like with China) that suppresses real interest rates or if you have a great depression type scenario where the inflation rate is severely negative (massive deflation). In the massive deflation scenario real GDP may show growth while nominal GDP would show contraction. In the huge trade imbalance case real interest rates are suppressed by yield indifferent buyers - aka Mr. Alan Greenspan's bond conundrum and Mr. Ben Bernanke's global savings glut.

The way to get around both scenarios is to sell forward year tax receipts. A forward year tax receipt lowers the after tax cost of credit in the private sector while not depriving the bondholder of income. In a true great depression massive deflation type scenario even tax cuts don't have any traction because if nominal interest rates are 0, lowering the tax rate would have no effect on either money velocity or GDP.

What is a forward year tax receipt (FYTR)? It is a receipt for taxes paid in advance that are due some time in the future. Like federal government bonds, FYTR's have a duration and a rate of appreciation. Unlike federal debt, the rate of return is not guaranteed to the owner. The owner of the FYTR must have the tax liability to realize the appreciation.

= Outstanding Supply of Forward Year Tax Receipts

= Outstanding Supply of Forward Year Tax Receipts

= Forward Year Tax Receipt Rate of Appreciation

= Forward Year Tax Receipt Rate of Appreciation

The next thing we express is how the level of debt is related to the level of FYTR's by some constant of multiplication called

: This constant L is at the discretion of the federal government, how many FYTR's do they want to sell in relation to how much outstanding debt there is. Obviously there are limits to

: This constant L is at the discretion of the federal government, how many FYTR's do they want to sell in relation to how much outstanding debt there is. Obviously there are limits to  based upon how much demand there is for them and how they are priced.

based upon how much demand there is for them and how they are priced.

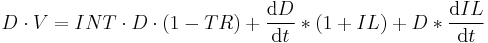

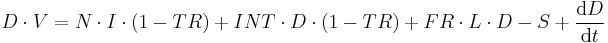

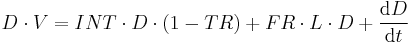

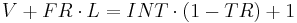

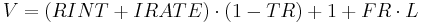

And so back to our finance equation:

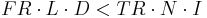

Note: One thing to be aware of is that the realizable gains from forward year tax receipts can never exceed the total tax receipts in the same year or:

Again, in a closed economy (no foreign trade), the after tax non-interest income per year will equal the savings per year.

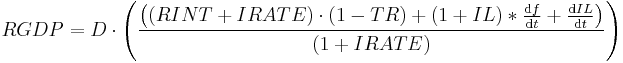

Solving the differential equation for D:

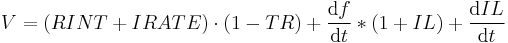

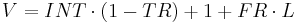

Again, the interest rate has a real and inflation component, and so breaking up the interest rate into its components gives:

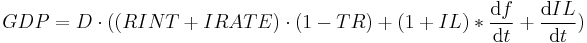

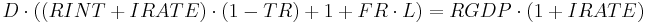

Back to the Fisher equation:

![RGDP = [D \cdot ((RINT %2B IRATE) \cdot (1 - TR) %2B 1 %2B FR \cdot FO] / [1 %2B IRATE])](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fb04f1bc03bb0795cf9d330c6a7d97fb.png)

![GDP = [D \cdot ((RINT %2B IRATE) \cdot (1 - TR) %2B 1) %2B FR \cdot FO] / [1 %2B IRATE])](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0dd30f97d32c630bcb29cb75925a9465.png)

The beauty here is that in a mass deflation scenario both nominal and real gross domestic product hold can be pushed higher by lowering the after tax cost of capital in the private sector. See equations above: even if the inflation rate was say -10%, the  rate could be set by the federal government to be + 15% -- real GDP growth, nominal GDP growth, presumably rising employment and deflation to boot.

rate could be set by the federal government to be + 15% -- real GDP growth, nominal GDP growth, presumably rising employment and deflation to boot.

See also

- Consumption smoothing

- Income#Meaning in economics and use in economic theory

- Milton Friedman

- Ricardian equivalence

External links

- Robert Schenk, "Permanent-Income Hypothesis"

|

|||||||||||